Arthur C. Clarke: Imagining a future of hope in even the toughest of times

When The Hollywood Reporter broke the news in late December 2021 that Canadian auteur, Denis Villeneuve, would direct a movie version of Rendezvous with Rama, Arthur C. Clarke’s science fiction classic, the bated breath of Clarke fans worldwide surely echoed through the hills of Tinseltown. Villeneuve’s bona fides, after all, included his rhapsodic take on Frank Herbert’s Dune, at the time still raking in millions of dollars at the box office and destined to claim six Academy Awards.

“My reaction was just kind of like, ‘Oh, wow! I have been waiting my whole life for a movie of Rama and Villeneuve’s doing it,’” says Erik Viirre, a professor of neurosciences and director of the Arthur C. Clarke Center for Human Imagination at University of California, San Diego. The Center operates under the auspices of the Arthur C. Clarke Foundation, and “engages imagination as a fundamental human capacity to be understood, developed, and brought to bear on the world’s biggest problems.”

Clarke fans like Viirre have set a high bar for the film—but then again, so did Clarke, whose collaboration with the late director Stanley Kubrick resulted in the 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Even today, the film looks and feels both astonishingly accurate and futuristic and, for many devotees of the genre, will never be rivaled.

But no matter how Villeneuve’s film turns out, Clarke’s high-priest status in the pantheon of 20th Century science fiction writers endures. Over the course of six decades, he authored 100 books, 200 short stories, and numerous essays. His undergraduate degree in physics and passion for astronomy and other sciences lent authority to his compelling, awe-inspiring visions of the future. He became something of a spokesman for science and space travel when he provided commentary for the Apollo XI Moon Landing, among other ventures in popularizing science.

As just one example of his prescience, Viirre cites Clarke’s 1953 novel, Childhood’s End, in which the author describes immersive visual experiences like today’s AR/VR technology—“which is kind of mind-boggling in a time even before computer screens,” he says.

Clarke is also credited with giving Kubrick the idea of streaming visual readouts on computer screens in 2001, a special effect that had to be painstakingly filmed—because there was no such thing. Both Kubrick and Clarke were dedicated to a realistic portrayal of the future in 2001, notes Viirre. They even tossed in some branding of their future technologies using, for example, IBM for the computers and Frigidaire for the food dispensers onboard the movie’s Jupiter-bound spacecraft.

Science wasn’t just a hobby for Clarke, Viirre says. He served as an engineering physicist for the British Ministry of Defense in World War II. “He worked on radar and in fact, his signal invention, often called the Clarke Orbit, was the concept of the geosynchronous orbit [for satellite communications], published in Wireless World magazine in 1946. And he also published a textbook on astronautics in 1948. I have a first edition of that.”

After the war, Clarke moved to Sri Lanka, then known as Ceylon, and became an avid scuba diver. “He went literally around the world diving,” Viirre says. For Clarke, weightlessness underwater was the closest he would ever get to the experience of being in space. He later advised NASA to use scuba to simulate space for astronauts.

Aspects of Viirre’s professional life follow Clarke’s footsteps. “Aerospace has been a big part of me and my career. I’m a specialist in gravity and gravity diseases. I’m a physician. I practice here at the university in the Department of Neurology, and I deal with inner-ear imbalances.”

Viirre’s encounters with Clarke’s work began early. “I was in the first class of International Space University, which was held in 1988 at MIT, and Clarke was our chancellor and convocation speaker that summer.”

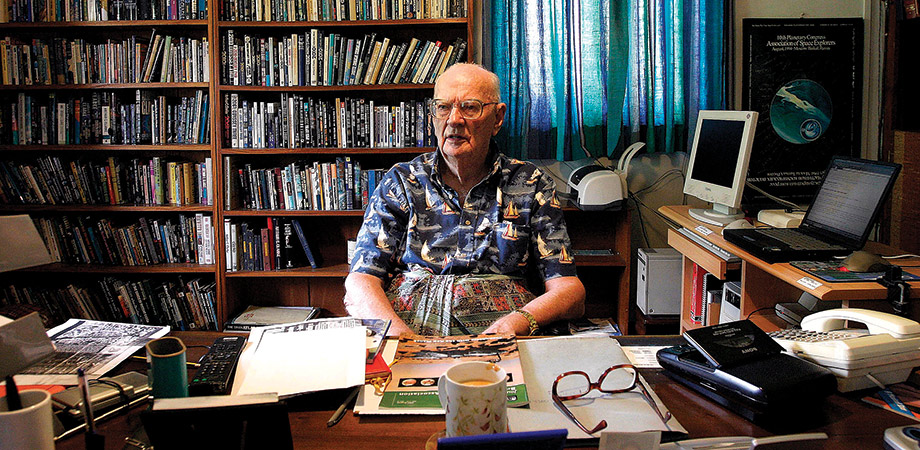

Viirre with Clarke at his home in Sri Lanka. Photo credit: Erik Viirre

At the Clarke Center, he says, “we’re interested in the faculty of imagination, its operation in humans, and then embracing and enhancing imagination through a variety of initiatives. In a very Clarke-ian way, we have a core of our center called Speculative Futures, which of course embraces science fiction. We host the pre-eminent Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop, which was originally founded almost 50 years ago by Harlan Ellison,” Viirre continues. “It’s an in-residence summer program for aspiring science fiction writers”.

Another very Clarke-ian pillar of the Center is called “To the Stars.” Anticipating widespread colonization of space, the project encompasses studies of the effects of weightlessness on human biology, especially the brain.

A few years before Clarke’s death in 2008, at the age of 90, Viirre visited him in Sri Lanka, an experience he describes as one of the most significant in his life. Sadly, an earlier-in-life bout with polio had returned, and Clarke was in a wheelchair. Nonetheless, Viirre found the esteemed writer and futurist engaged and engaging.

At one point, Viirre asked Clarke about a pact that supposedly existed with fellow science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. It went something like, “if somebody asked Clarke who was the greatest science fiction writer, he would say Asimov, and crown himself a close second. And if Asimov was asked that question, he would say Clarke. I asked him to verify the pact and he said it was true.”

“If I was able to quietly ask Clarke one more question,” adds Viirre, “it would be if he knew about [codebreaker and war hero] Alan Turing, and whether he knew what happened to Turing, because as you recall, at that time in the UK, thousands of men were arrested and charged for being homosexual.” Turing committed suicide in 1954, following his 1952 arrest and conviction.

“My quiet suspicion,” Viirre says, “is that that was one of the reasons Clarke went and left the UK after the war. For the rest of his life, Clarke worked globally. And so, as with many gay men, you know, these things were sort of quietly avoided, in all levels of society, both in the United States and the UK.”

Despite living through one of the darkest chapters in human history, however, Viirre says Clarke emerged from World War II an optimist, and his vision for humanity was one of optimism. He says Clarke’s outlook was exemplified by his 1960 work of nonfiction, Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible. Viirre says it became a touchstone for his life.

“I have an original edition and it was updated throughout the years until the year 2000. It shows Clarke as very much an optimist. It’s a romp through science—theories of gravity, physics, chemistry, space travel, and all kinds of other things. When I’m looking for inspiration, I go back to it. And, not only because of his prescience in what he saw in the future, but just for his way of thinking about it. [Clarke] was absolutely a believer in humanity and, in these tough times, it’s tough to adopt that kind of spirit, but we need to.”

William G. Schulz is Managing Editor of Photonics Focus.

| Enjoy this article? Get similar news in your inbox |

|